To get a glimpse of what the book is like, a few paragraphs have been translated. Note that these translations have not been done by a professional translator.

First paragraph

LaGuardia Airport New York,

February 14, 1946

Flat, brown leather shoes with laces. That’s what Gerda Nothmann wore with her dress on the day she first set foot on the soil of her new homeland. The shoes were part of the two sets of clothing that Gerda was allowed to pick after the liberation: one set given to her by the Dutch Government, the other one by the Dutch electronics firm Philips in Eindhoven.

Though the other women of her group were overjoyed to get themselves a pair of elegant, high-heeled shoes, eighteen-year-old Gerda chose the most solid pair she could find. That seemed to her like the most sensible choice for the future. After all, one could never know when a pair of sturdy shoes might come in handy again.

About Gerda having to part from her beloved foster family in Camp Vught

Up until the last moment, Gerda had begged her foster mother to let her join them on transport. But ‘Moekie’ had been unrelenting: ‘[She] told me that my hope for survival lay in remaining in Vught and working for Philips.’ Because of her work as a camp doctor, Käthe could have stayed too, but she chose to go with her family. On Friday, July 2, 1943, the transport with on board, amongst others, the Deen family left from the station in Vught. That same day, ‘hurriedly in between packing,’ Helga wrote a letter to her friends in Tilburg. She sounded hopeful when she mentioned a new Sperrung[1] that could mean she could stay in Westerbork: ‘I don’t feel any nervousness, nor do any of the others, we are healthy, happy and tough and are facing what is to come with our best optimism.’ In her diary, Helga doesn’t describe how it was for her to say goodbye to Gerda. But forty-five years later, in her memoir, Gerda wrote about what the goodbye did to her:

‘Their departure from Vught, our parting, stands out in my mind as the single most difficult moment of my life. One moment I was part of a family. The next moment, I was alone, utterly and totally alone. It was the trauma of my life.’

In an interview in 1995, she once again spoke about the goodbye:

‘I died. […] I became stone. I stopped feeling, I stopped being a human being. The shock was so great of losing them, of being alone there. Something very bad happened to me, in myself. I just didn’t connect to anybody anymore. I became a robot, but I carried on.’

[1] German word which means in this context being protected from transport.

About the bravura of the Philips-employees in Camp Vught

The longer the workshop was in use, the more difficult it became to fool everybody. SS officer Titho (who the Kommando members, against all camp rules, greeted with ‘Hello, Tito’[1]) was fairly good willed towards the Philips Kommando. He too, however, would speak of ‘the most lazy, the most overfed and the most anti-German workforce of the entire camp.’ Judging by how Klaartje de Zwarte described her first day in the Philips workshop in her diary, he didn’t seem to be so wrong about that:

‘When I joined the Philips, I right away just took the liberty to rest myself a little. I bent over the table and rested my head on my arms and even though I couldn’t sleep, it did make me feel good for a brief moment […] I already knew I would be admitted to the workforce and I didn’t feel like I had to put in any more effort […] Again, I got a bowl of delicious porridge and I let myself be pampered all day long. The hours flew by and every once in a while officers came in to see how our work was progressing. At such times we would put on quite the show. The foreman stood to attention and everyone pretended to be hard at work. But the officers had only barely left the room, and already we had put an end to the show, putting our soldering irons down and continuing our conversations.’

Even charismatic Braakman had more and more trouble upholding the credibility of the Philips workshop. Often, his courage verged on recklessness. One day, he got himself into quite a fix when he hid his own radio – which he should have handed in like any other Dutchman – in the workshop in Camp Vught. What better place to hide it, he reasoned, than in the belly of the beast. But soon after, the work barracks were inspected outside working hours and the radio was discovered. Everyone panicked, except Braakman himself.

First, he calmly assessed what damage had been done. Then, his motto being ‘attack is the best form of defense,’ he went to the camp commander. Indignantly, he complained about the destruction that was caused during the inspection and the goods that were taken. When bluntly confronted with the radio that had been discovered and that even had his name on it, he had his story prepared. In the factories in Eindhoven, he said, it had been found that listening to light music for a couple of hours a day increased the productivity at work. At the workshop, they were now working on developing a similar broadcasting system for the entire camp. Wasn’t that just great? This radio was the main unit, and either today or tomorrow they were going to establish connections to the work barracks, filling the entire camp with marching music.

With this explanation, Braakman managed to stay out of further trouble. However, there was no way back for him now and the broadcasting system had to actually be installed. And so it happened that on Christmas Eve of 1943, the eleven members of the Netherlands Marechaussee Brigade Grootegast, who were imprisoned after they had refused to arrest Jews, sang Christmas carols through the intercom.

[1] The spelling of the name is different in this phrase, which makes the pronunciation a bit different in Dutch. This way of pronouncing makes the greeting sound mocking, because of the rhime (‘Hallo Tito’).

About the arrival of the women of the Philips-group in Sweden

Major Weibull gave the representatives of the different countries their final instructions. The stretchers had been readied. The Swedish Lottas, members of the Women’s Voluntary Defense Service Lotta Svärd, stood in their gray uniforms behind baskets of bread and steaming pots filled with hot chocolate. The wharf was swarmed with people; some even leaning out of the windows of the surrounding houses. Suddenly, the excited buzz fell silent: the ferry came sailing into the port.

When, on May 4, 1945, the last boat with so-called ‘white bus refugees’ pulled into the Färjestation, the people of the Swedish city Malmö had already seen their fair share of boats carrying former concentration camp prisoners. But just like all the other times, those present were once again struck by, as an eyewitness described it, ‘the immensity of the moment.’ The Dutch representation on site, consisting of four men, had learned that the Dutch prisoners would be on the ferry’s aft deck. So when the boat docked, they pressed their way to the ship’s railing:

‘But we didn’t see any Dutch people, we only saw a large group of gypsies of an unspeakably low nature; skinny, pale blue individuals, dirty, dressed in rags, some without stockings, others with shreds of burlap wrapped around their feet, a ragged throng of people. ‘Aren’t there any Dutch people here?,’ we yelled. Now, what kind of secret word had we just used? The gypsies erupted in a clamor of shouts and screams. They waved their dirty blankets and unsightly bundles of clothes. ‘Dutch, Dutch,’ they called out. Dear Lord, so these were the Philips and diamond groups, the large contingent of Jewish Dutch women. I swallowed hard, we waved, we shouted: “Welcome!”’

In response to the welcome of the Dutch delegation, the women started singing the Dutch national anthem. The four men were moved to tears. ‘Skittish like stray dogs,’ the women walked down the gangplank. ‘Their walking was more like hopping, stumbling, hastily like they were afraid to miss their train.’ Once on the mainland, the women looked around suspiciously as if they feared their luck could turn any moment. ‘Welcome to Sweden,’ the men from the Dutch delegation repeated. And it was only then that the women smiled, ‘like the sun broke through dark clouds.’

Memoirs

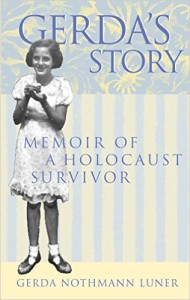

Gerda wrote her memoirs originally in English. The memoirs, together with a text by Gerda’s husband Charles Luner, are published in Gerda’s Story. The Memoir of a Holocaust Survivor:

Click here to buy Gerda’s Story. (NB This is a different book from Philips-girl, which has not yet been translated into English)

News

Gerda’s daughter Vera gave an interview to a local radio station in St. Louis, about growing up with a mother who survived Auschwitz.